Research

My primary research agenda investigates: How do healthcare technologies impact health(care) quality and disparities in the U.S.?

I explore this question through my dissertation and in work published in the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities on disparities in the use of personal health technologies based on past healthcare encounters. In one dissertation paper, I explore how patients use personal health technologies (e.g., smart watches, health apps) to navigate their healthcare interactions and improve their sense of agency and shared decision making. In the second paper, which uses originally collected data from a video vignette survey experiment, I examine provider bias in data entry into the clinical record, with implications for the use of those records for AI driven research. In the third paper, I explore patterns in the adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) by hospital systems in the US and aim to examine if adoption patterns correlate with change in healthcare quality at the state level.

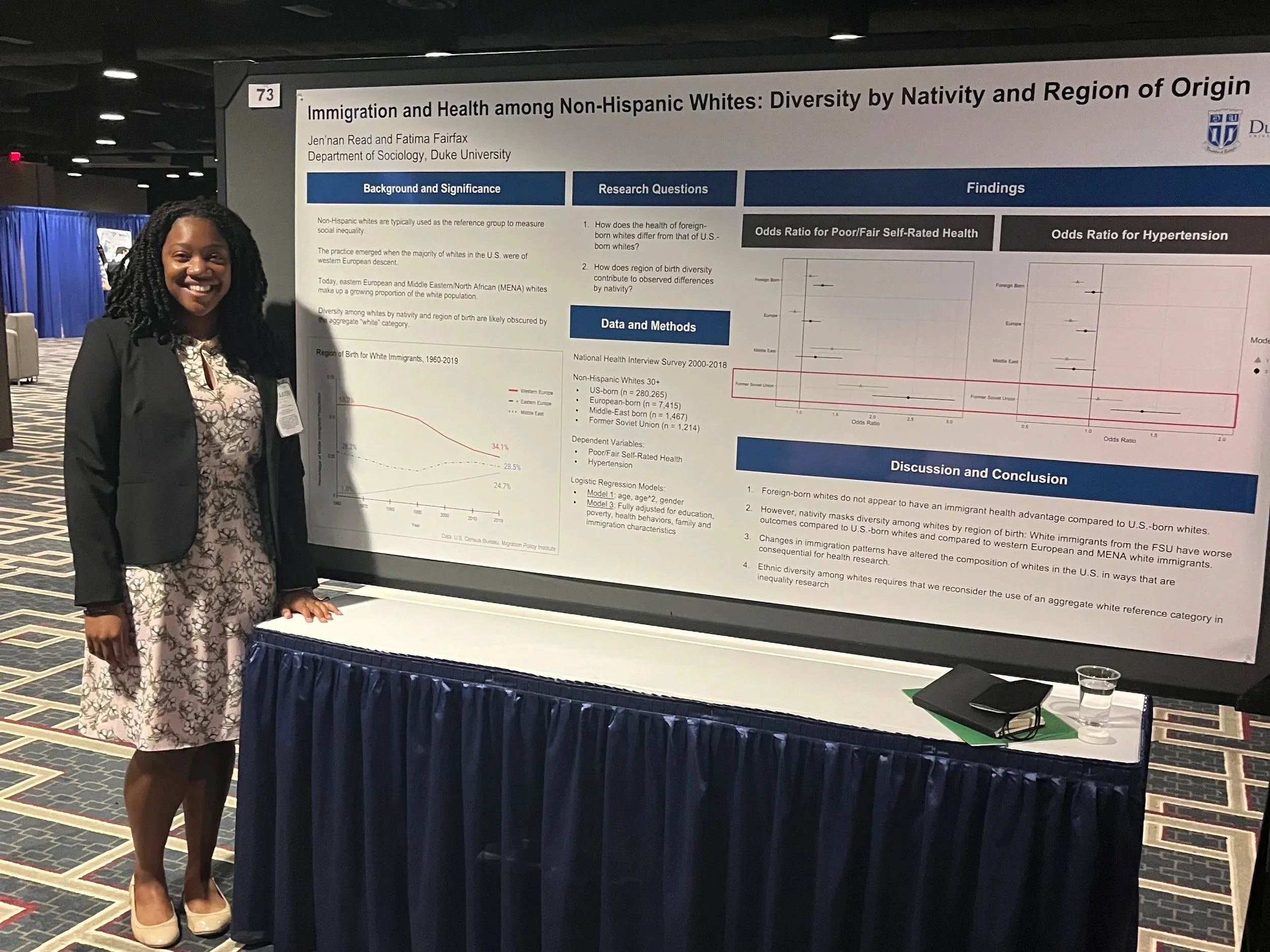

Beyond health technologies, I also explore how race is conceptualized and measured in health research, and how this may inform our knowledge of health disparities and mechanisms of health inequities. In work published in Demography with co-author Jen’nan Read, we explore how the ethnic composition of the white racial category has shifted over time and what implications this might have for the default reference category (non-Hispanic white) in health research. In other ongoing work, I am working on a manuscript that explores how “street-race,” or the race that is ascribed to individuals by other people, can complicate how we understand racial disparities in mental health outcomes among marginalized racial groups.

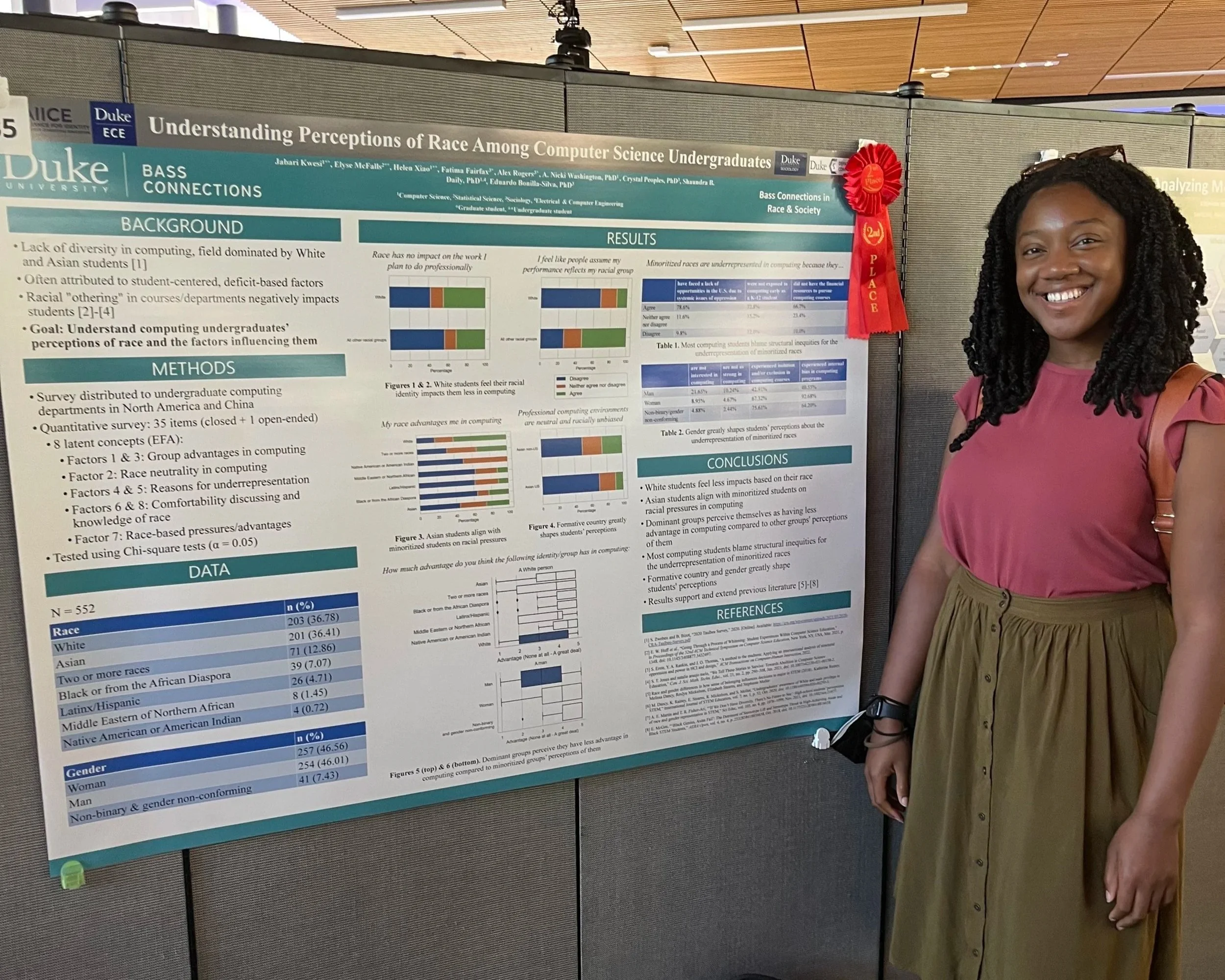

A third major stream of research centers on how emerging technology developers (i.e., post-secondary computing students) make sense of race and racism in university computing departments, the computing workforce, and technology. Our multidisciplinary research team, situated in Duke’s AiiCE, designed and conducted an original mixed-methods study, consisting of surveys and in-depth interviews, with post-secondary computing students to examine their experiences with race and racism in computer science, as well as their perspectives on race-conscious policies and practices. In published conference papers, we show that conversations about race among computer science students are associated with their perceptions of the disadvantages faced by marginalized groups in the field. Moreover, the influence of these conversations on how students make sense of (dis)advantage varies by their race and gender identity.

Several manuscripts are underway focusing on the qualitative data from this study, in which we investigate how students make sense of race and racism in computing, how that manifests in their beliefs about racism in technologies and the computing workforce, and how, if at all, the opinions of computing students have changed since the 2023 SCOTUS decision banning race-based admissions policies in higher education.

Recent Publications

-

The widespread adoption of personal health devices has introduced a new source of health data for patients and providers to use in healthcare settings. Using patient-generated health data (PGHD) in healthcare settings has been found to improve patient-provider interactions and care outcomes. However, rates of PGHD sharing vary across the population. The decision to share one’s PGHD with providers is influenced by past healthcare encounters including quality of care, medical mistrust, and healthcare discrimination. Furthermore, those experiences and patients’ responses to them should be examined with an intersectional lens to acknowledge how gendered racism impacts health and healthcare. Using the 2022 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) and logistic regression, this study shows how racial discrimination, healthcare quality, and medical mistrust are associated with patients’ willingness and decision to share PGHD with providers among different race-gender identities. Factors associated with patients’ perceived willingness to share data are not the same factors that are associated with actually sharing PGHD with providers. Perceived racial discrimination in healthcare settings was only significantly associated with willingness to share PGHD among Black men and white men. Meanwhile, poor overall healthcare quality was significantly associated with incidences of sharing data among Black and Hispanic women. These varied patterns across intent to share and choice to share, as well as across race-gender identity, reveal important insights into barriers to effective integration of PGHD in clinical spaces and the use of this technology to address healthcare inequities.

-

Inequality research has often used non-Hispanic Whites as the reference category in measuring U.S. racial and ethnic health disparities, with less attention paid to diversity among Whites. Immigration patterns over the last several decades have led to greater ethnic heterogeneity among Whites, which could be hidden by the aggregate category. Using data from the National Health Interview Survey (2000–2018), we disaggregate non-Hispanic Whites by nativity status (U.S.- and foreign-born) and foreign-born region of birth (Europe, Former Soviet Union, and the Middle East) to examine diversity in health among adults aged 30+ (n = 290,361). We find that foreign-born Whites do not have a consistent immigrant health advantage over U.S.-born Whites, and the presence of an advantage further varies by birth region. Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) are particularly disadvantaged, reporting worse self-rated health and higher rates of hypertension (high blood pressure) than U.S.-born and European-born Whites. Middle Eastern immigrants also fare worse than U.S.-born Whites but have health outcomes more similar to European immigrants than to immigrants from the FSU. These findings highlight considerable diversity in health among White subgroups that is masked by the aggregate White category. Future research must continue to monitor growing heterogeneity among Whites and consider more carefully their use as an aggregate category for gauging racial inequality.